Breasts. The word alone conjures notions that range from the maternal to the pornographic. Whether they’re and A, B, C, D or beyond, breasts are fraught with complicated and often conflicting desires. So what is it that gives these glands, totally devoid of muscle, such incredible power?

As a culture, we are breast obsessed. To be sure, nearly 38,000 breast augmentations were performed by AACS members in 2009 alone. Our lingerie models, reality stars and even cartoon characters are increasingly sporting chests of epic—if not unbelievable—proportions. But while Christina Hendricks-like curves may have their perks (pun intended), the power of those breasts on the way a woman feels about herself and interacts with others is complicated by instincts and contemporary values that don’t always match up.

According to Christopher Ryan, coauthor of New York Times best seller Sex At Dawn: The Prehistoric Origins of Modern Sexuality and an expert in evolutionary psychology, the “power” of breasts originates in their prehistoric function as “sexual swellings,” natural augmentations that advertised a woman’s biological availability during ovulation. “Full breasts,” explains Ryan, “are attractive to men because they signal youth and fertility,” adding, “as a woman’s fertility fades with age, so do her breasts.”

Unlike our ancestors, however, Ryan suggests that breasts as sexual swellings are intended to create and maintain relationships, versus just reproduction. Our desire to prop, pad and surgically augment our breasts is thus a carry-over from ancient times, something we are prehistorically conditioned to do for companionship, if not sex.

A Proverbial Jungle

Ryan specifically likens the way a woman might use her breasts strategically to the way many men buy expensive watches, cars and clothing in the hopes of making themselves more attractive “mates.”

“Women experience the power that pendulous breasts give them (or don’t) in their interactions with men,” explains Ryan, “So it is utterly normal that many women will opt to increase this power if they can.”

And they almost always can. From 18th-century corsets to the latest Victoria’s Secret cleavage-creator to surgical options, fashion trends and technologies have supported women in their quest for curves for centuries. “Sex today requires a lot of negotiation,” asserts Ryan. And while the particulars of how we use our breasts in the mating process may have changed, “We are still primates,” he says, “and it’s a jungle out there.”

But the particulars of the jungle have also changed. The appeal of breasts today is no longer just a matter of their subconscious function in mating, but rather their very conscious perception and depiction as eye-popping, jawdropping sexual objects.

“Breasts have an inherent biological appeal to men,” states Ryan, “but they have been eroticized through the taboo.” Recalling the role of women’s ankles in Victorian England, Ryan explains how the obligation to cover a body part has the paradoxical effect of making it extremely sexy. The forbidden fruit of our time, the breasts have been sexualized in America because of the taboo, and sometimes shame, we’ve culturally ascribed to them. This fact is underscored when you compare the American preoccupation with breasts to that in Europe, where bare breasts are frequently shown in advertisements and are perceived as nice, but not, in the words of Ryan “such a big deal.”

Great Power, Great Responsibility

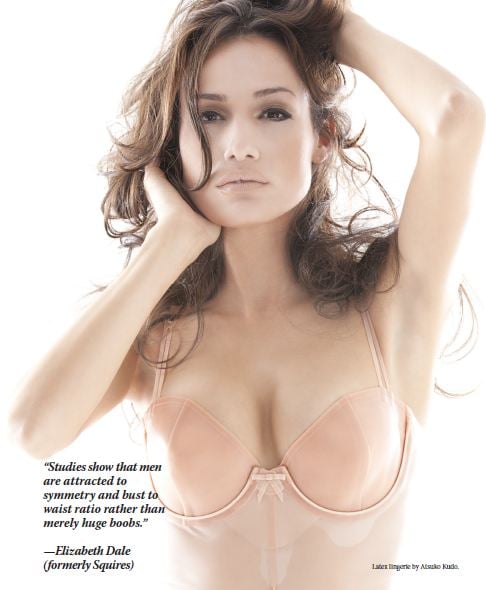

Elisabeth Dale (formerly Squires), author of Boobs: A Guide to Your Girls and an expert on women’s relationships to their breasts, agrees. “The sexualization of breasts is rampant in the media,” says Dale, “but rather than celebrate their power, we trivialize breasts because we are afraid to admit this power.” The fact that we refer to someone stupid as a “boob,” she explains, demonstrates how our society has preferred to trivialize breasts rather than admit to their potency. Breast augmentation, Dale explains, is similarly mocked by mainstream media as a way of denying the powerful allure of breasts in favor of their sacred and maternal depiction.

For the modern woman, juggling family, work and her own femininity, the popular discomfort surrounding breasts does have its consequences. In fact, a study cited by Dale on breasts in the workplace revealed that men view large-breasted women as less personable and less professional than their average-breasted colleagues. Similarly, Dale points to the discrimination that can occur between women of different breast sizes as evidence of some of the downsides to big breasts.

“Breasts are the only thing that attract and distract at the same time,” says Dale. “We have to remember that while more women are showing more cleavage, you really have to use your breast power responsibly.”

Despite the potential drawbacks, breast size is increasing across the board. “E cup is the new C cup,” says Dale of the fact women are getting bigger, earlier than ever. Environment, lifestyle and a sustained boom in breast augmentation procedures all contribute to the growing American bosom. Perhaps not surprisingly, this is especially true in warm regions in the U.S.

“In the Silicone Sunbelt, regions where it is warm year-round, women get implants that are approximately 200 ccs larger compared with elsewhere,” explains Dale. Of course, less clothing and more beach time in the warm weather not only makes breasts more visible but also increases their power in the relationship dynamics described by Ryan.

Power in Proportion

But breast appeal is not just a matter of size. Indeed, there are more than a few celebrity examples of “too big” and Dale insists that disproportionately bigger does not

And while Dolly Parton-esque breasts may turn heads, Dale suggests that they may literally be too much for men to handle: “Men like steak. Of course, if you put a 24 oz. steak in front of him he is going to salivate for it but does that mean that he can or wants to eat it all? No.”

Michael Kluksa, MD, a plastic surgeon based in Greensburg, Pa., similarly dismisses the idea that one size fits all when it comes to the ideal breasts. “Over the years, Victoria’s Secret leading the way, the media has convinced us all that every woman should be a 34 C,” explains Dr. Kluska. “I try to convince my patients to get whatever breast [size] will match the proportions of her shoulders, waists and hips.”

While most of Dr. Kluska’s patients come out a C or D cup, he is mindful of body type as well as size when plotting an augmentation. “A full-figured woman is going to have an entirely different type of breast than a smaller girl,” says Dr. Kluska.

Size aside, women also have different ideas about how they want their breasts to look. “Most women want a very symmetrical, well-rounded breast, but some women will come in and want their breasts more perky or with more volume,” Dr. Kluska says. To achieve the necessary variety of breast aesthetics, Dr. Kluska uses low-, moderate- and high-profile implants, which enable him to custom fit each augmentation to his patients’ wishes.

Patient desires are increasingly personalized. Despite the Hollywood stereotypes, the average breast augmentation patient is seeking to restore a former fullness rather than an unnatural inflation.

According to Dale, “The typical patient is a 33-year-old woman, with two children and a college education. She isn’t looking to augment as much as return to her previous shape and size,” says Dale. In addition to the “mommy” subset described by Dale, Dr. Kluska says many younger women come in seeking augmentation because they are self-conscious about having small breasts. “She hasn’t had kids but never had breasts in high school and may have been made fun of because of it,” Dr. Kluska explains. “These patients really gain a lot of self esteem from augmentation.”

But not all women seeking surgery to improve the way they feel about their breasts go bigger. Dr. Kluska says that many women with large breasts seek a reduction to minimize the attention they attract.

“These women want to be viewed as a whole person, not just a woman with huge breasts,” he says.

To be sure, women who have reductions are, according to Dale, the happiest breast surgery patients despite aesthetic outcomes. There are certainly therapeutic benefits to some reductions including relief of neck, head and back tension. But more—or at least in addition to the physical benefits—Dr. Kluska believes the satisfaction stems from how a woman feels about herself. “I think that the biggest thing women gain from breasts—nice-looking not necessarily big—is that feeling of self esteem.”

Personal Power

Whether a woman is going from small to bigger or big to smaller, the decision to surgically alter her breasts is chiefly motivated by how her breasts make her feel. While fashion trends and the media influence what a woman may conceive of as the ideal shape or size, the pursuit of this ideal is increasingly about self-fulfillment. The stereotype of pushy husbands or boyfriends forcing women to cup sizes above or beyond is simply not the norm in a society where women are more empowered and autonomous than ever.

“Women are doing this for themselves,” explains Dr. Kluska of his breast patients. “They come in when the timing in their lives is right.”

And this speaks to the real power of breasts—the power that is claimed by she who owns them, she who flaunts them, conceals them, grows them and shrinks them. Though prehistory, men and Victoria’s Secret billboards may influence the particulars of their allure, the power of breasts is something specific to the woman who wears them—however she may do so and whomever she may share them with.