Carmen Dell’orefice is the picture of enduring grace and taste.

BY Ruchel Louis Coetzee

PHOTOGRAPH by Richard Avedon © The Richard Avedon Foundation (right)

PHOTOGRAPHS by © Norman Parkinson Ltd/Courtesy Norman Parkinson Archive (this page); Fadil Berisha (center)

Dell’orefice in “new holiday looks in the bahamas,” British Vogue, July 1959 PHOTOGRAPH by Norman Parkinson (left)

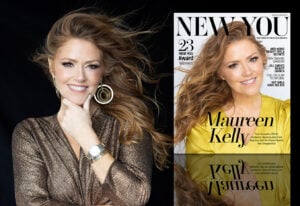

I HAVE A TIMELESS MENTALITY,” insists Carmen Dell’Orefice, the iconic fashion model whose image first graced Vogue’s cover when she was just 15 years old. “We’re all works of art in progress. I’m still figuring out how to do the job, and who I am.”

Mysteries aside, some facts surrounding this sophisticated beauty are astounding: She’s now 82 and has had more covers in the past 15 years than at any other time in her career. Designers Galliano, Gaultier, and Mugler still call her to walk their runways. And somehow, despite the long and winding road of her life, she still considers the fashion world—her world—to be rooted in la dolce vita.

The only child of a Hungarian mother and Italian father who seldom lived together, Dell’Orefice looks back on her modeling career as “an odd privilege.” She imagines, in retrospect, that she should have taken up Salvador Dali’s offer to carry off the animal sketches lying on his floor in lieu of the $7.50 modeling fee she commanded at age 13. “I was working with Cecil Beaton at Vogue, and he thought I should meet this painter,” she recalls. “He requested that I go home and ask my mother’s permission.” The name Salvador Dali meant nothing to her mother, who worked full time to make ends meet. The extra money did, however, and permission was granted. After lunch at the St. Regis, Beaton left Dell’Orefice alone with Dali in his hotel suite. “Dali wanted me nude from the waist up,” she says. Being near starvation-thin at the time, with no sign of a bust, Carmen agreed, rationalizing that she had nothing to hide. After several days, the painting was complete and she was thrilled to see that Dali’s paints provided what nature had neglected. Lord Mountbatten, the Earl Mountbatten of Burma, bought the painting as a wedding present for the Queen of England. It now resides at Buckingham Palace.

On this overcast autumn afternoon in New York City, Dell’Orefice sits with the poise of a swan in her eclectic Park Avenue apartment, sipping Evian through a straw. She is astonishingly lovely—her trademark silver mane framing high cheekbones and expressive almond eyes, her taut skin absent of any sag, thanks to regular silicone injections and a healthy approach to life. “Frail” and “old” have not dared enter the room, despite having recently undergone two knee operations. On the walls and in picture frames are photos spanning her 70-year modeling career—photos taken by Beaton, Richard Avedon, and Mario Testino. We’d be hard pressed to find another model whose career holds a candle to such history. “Everybody tells me how wonderful it is,” she says of her career. “They don’t have the knowledge I have—the peace inside. When you understand how to do that dance, when the photographer says, ‘Hold it, do it,’ and you know you’re getting it right. Oh, the fun. It is fun.”

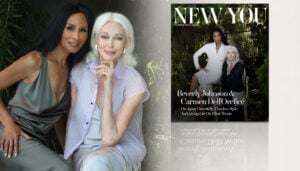

“Getting it right” is an important concept for Dell’Orefice. Ford’s longest working model (since 1947), she is humbled by how in demand she remains. Recently, the agency for clothing line The Row—established by Mary-Kate and Ashley Olsen—called to request a fitting. This came after a trip to Austria where students of the Fashion Council in Vienna had designed clothes specifically for her to model. In the past year, she has graced the cover of Italian Vogue, been the face of Rolex, and appeared regularly in ad campaigns within Vogue, W, and Harper’s Bazaar. “Carmen is one of those rare human beings,” declares Beverly Johnson, the first African American model to appear on the cover of American Vogue. “Not only does she get smarter, wittier, and more accessible, she’s become more physically beautiful and graceful every day.”

Dell’Orefice’s vivid ruminations range from upper-crust happenings at the Russian Tea Room and the Carlyle to the stylish side streets of Paris and London. One subject she knows best: the special relationship shared between a photographer and a model. “It’s like having a quickie,” she laughs. “It’s a very sensual experience. Avedon was always in charge—he had already seen the clothes in Paris. Norman Parkinson was in charge. The one who was a little bit higher and more in control was Alexey Brodovitch, or [Alexander] Liberman—those old art directors who showed other photographers what to look at, how light falls on an object, what the picture was in their head, and how it could be created.”

THESE DAYS, DELL’OREFICE DOESN’T KNOW the art directors. “I see some things I like,” she admits. “I love Ralph Lauren’s marketing—the ladies he chooses, even his young ladies, have a sense of quality. They can be innocent but aren’t vulgar. Stylists in my day were lady editors, and the way they dressed was the message.”

She also remembers the distinct separation of rich and poor prior to World War II, and how the rise of the middle class allowed fashion to become available to a wider demographic. “There’s great style to pick from now, because during World War II—when the rich couldn’t go to Europe for their seasonal wardrobe—America started making something called ‘separates,’” she notes. Dell’Orefice mentions Halston and Donna Karan as two of her favorite designers. “They tend to make things that are going to fit me, because they design long,” she says. “I see shoes today that I love but I can’t walk in them. I have the same problem all women do in finding what’s comfortable. However, fashion is so broad today, which is good. I now have choices.”

The elegance that permeates Dell’Orefice’s lifestyle sits in dramatic contrast to the meager assets of her childhood. “Beauty was the life preserver thrown to me when I most needed it, and I had no intention of throwing it away while still in the swim of things,” she reflects. Her mother was a Roxyette dancer—a predecessor to a Rockette—when she met her father, a concert violinist. An excellent athlete, Carmen’s mother taught her how to swim, in the hopes that she’d become a professional swimmer.

After several moves, Dell’Orefice and family settled into a small Manhattan apartment. There her mother arranged for Carmen to attend the best ballet school of the period, run by legends Maria and Vecheslav Swoboda. Though Carmen loved ballet and religiously practiced her pliés, rheumatic fever struck a year into training and she was relegated to bed. Swimming allowed her muscles to slowly heal. It was at this time that the wife of a staff photographer at Harper’s Bazaar approached Carmen on a bus and asked if she would agree to test photos. “She wanted to call my mother for permission, but we had no telephone,” says Carmen. The photographer of her first Vogue image considered her too thin, and shot her holding a cup of tea in front of her mouth to hide her braces and highlight her eyes. “As a child, I was silent,” she recalls. “But by 14, 15, I started to grow a bit taller and more physically strong.”

The discipline of competitive swimming and the deportment of ballet remain visible even today. They’ve carried her through decades of success, and to far-flung locales such as Paris, Rome, and Tahiti. “I kept growing into my profession; at certain moments, my look was in style,” she says. “But I’m not the ‘it’ girl. I was never a cover girl like Wilhelmina [Cooper] or Suzy Parker, neither an all-American or exotic girl. I was in between—very confident, and most successful when the clothes looked well on me or I was right for a collection.”

ON HER EIGHTEENTH birthday Carmen married the man she had fancied since age 16. His name was Bill Miles, age 26—already divorced, with a son. “Somebody once wrote that I retired; I did not retire,” insists Dell’Orefice. “I had a baby [daughter Laura], and worked when I was pregnant. Any job I could get in a flannel nightgown from Macy’s, I did.”

“I divorced [Miles] when Laura was about 4 or 5 years old, and went on to a brief marriage with photographer Richard Heimann, who was divine. It wasn’t just sex—it wasn’t that kind of love. I love physicality because I would dance and I was not uptight. I’m Italian!” Her third marriage to architect Richard Kaplan in the mid-sixties lasted 11 years, and she holds fond memories of her time with him.

An eternal romantic, she fell in love and was engaged to television talk-show host David Susskind, but he died before they were married. In the 1990s, there was Norman Levy, who introduced her to the lavish parties on yachts around the world with his best friend, Bernie Madoff. “Thank God he did not have to see the Madoff mess before he passed away.” she says. Through Madoff, she lost her life savings— a reality she brushes to the side while continuing to work.

That hard-won resilience is what carries Dell’Orefice through stormy seas, as well as the recollections of her many special friendships, with the likes of celebrated British photographer Norman Parkinson, CBE, whose notable portraits included those of Princess Anne and Queen Elizabeth. He will always hold a special place in her heart. On July 19, 2011, Carmen was awarded an honorary doctorate from the University of the Arts London, for her contribution to the fashion industry. Had Parkinson been alive, he would have acknowledged that the award was well deserved.

Today, Dell’Orefice insists on contentment and happiness at all costs. She loves to cook and rides an exercise cycle when her knee is not acting up. She also listens to her “energy” when she needs to feed her body, and always finds time to connect with friends such as Eileen Ford. As for fashion today? “The fashion business is not the same,” she says. “It’s lost its old-world glamour and civility.” That may be true but today Dell’Orefice remains as relevant as ever. ?